The Finger Lakes region in upper New York State is replete with long, deep lakes, old forests, tumbling waters, miles of vineyards, and last, but not least, women’s rights. I have been vacationing in the area ever since I participated in a conference at the Women’s Rights National Historical Park in Seneca Falls, where the First Women’s Rights Convention in the U.S. was held in 1848 . This area was home to a women’s rights and abolitionist reform community—led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott—who demanded equality with men in property rights, religion, marriage and family, and suffrage.

The Historical Park includes a Visitor Centre (in an old automobile showroom!), rebuilt Wesleyan Methodist Chapel where the Convention was held, and the homes of three of the local organizers, including Stanton’s house that is open to the public (see figure 1).

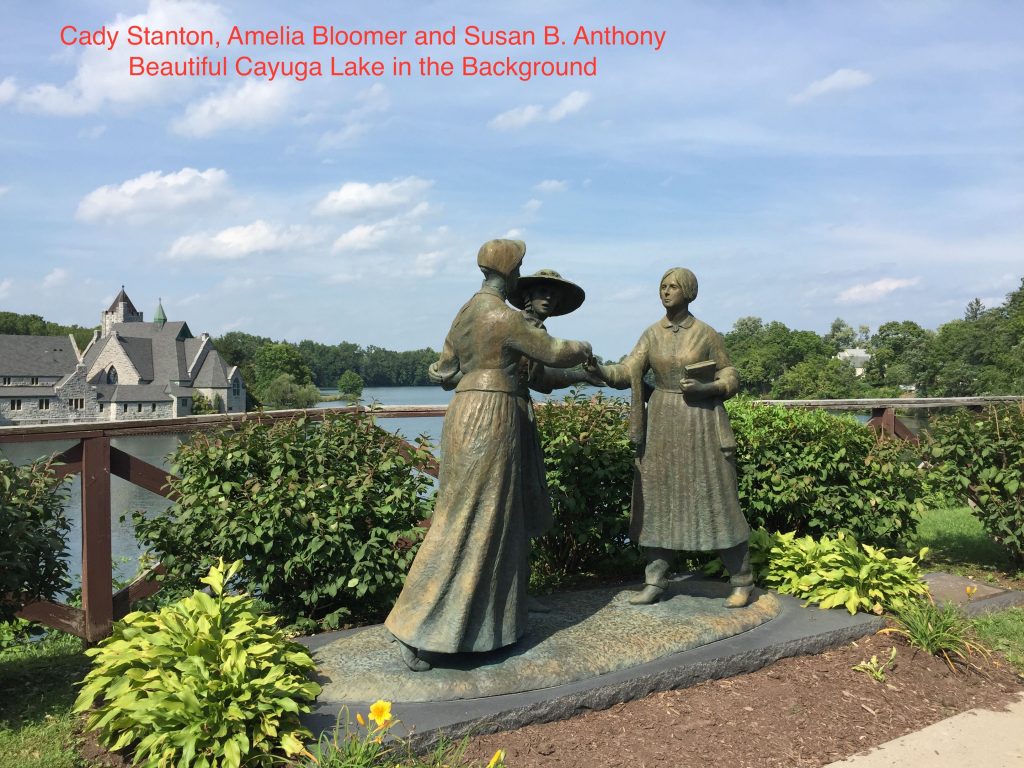

Also in Seneca Falls is the National Women’s Hall of Fame, which honors the achievements of important American women of all ethnicities in all fields and all eras, and a 1999 statue commemorating the 1851 meeting of Cady Stanton, Amelia Bloomer and Susan B. Anthony (Figure 2) Nearby are the home and gravesite of Harriet Tubman, ex-slave and heroine of the Underground Railroad, and, in Rochester, the National Susan B. Anthony House and Museum.

This summer, I returned to the Historical Park to check out their current exhibition, and here is a brief description. As you walk into the visitor center, you come face-to-face with life-size statues of twenty women and men, representing the 300 who participated in the Convention (including Frederick Douglass) (Figure 3).

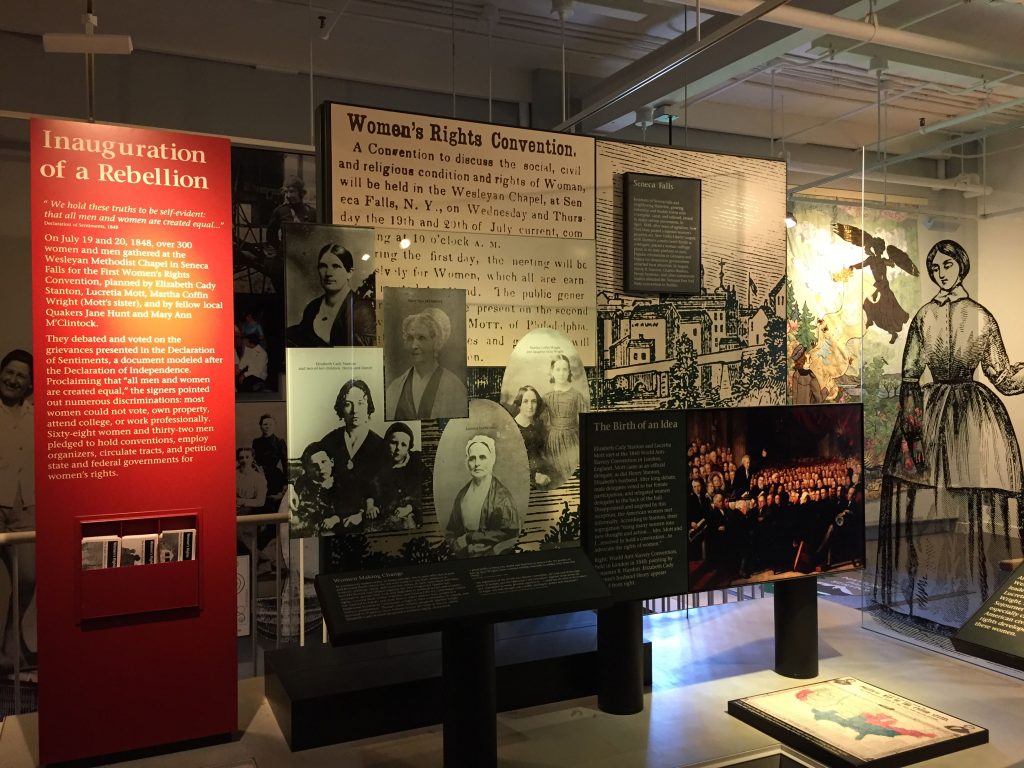

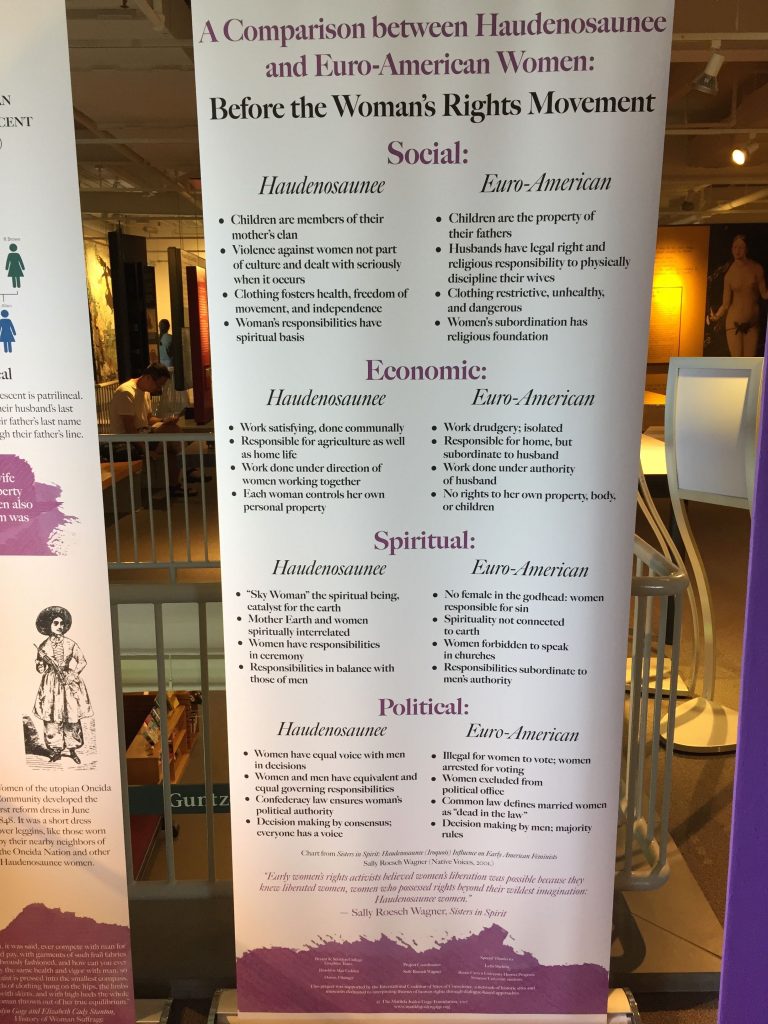

Upstairs, the exhibition gives background to the Convention and its nineteenth-century aftermath (figure 4), followed by somewhat arbitrary exhibits that swing from historical to contemporary on topics such as suffrage campaigns through history, women and sport, work, home, and dress; (somewhat idealized?) comparison between Haudenosaunee and European approach to women’s rights (figure 5); and a few interactives, such as “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

The exhibition space is small, and while it would be impossible to present a full examination of women’s rights reform, these disparate modules did not add up to presenting a cohesive picture of the 1848 Convention and its aftermath to today. The contents of the exhibits to my mind were big on blow-up images of people and text, and short on artifacts (figure 4).

I was sorry to see the disappearance of interactives from years back, including voting stations where visitors would watch a short video of people presenting both sides to an issue such as Affirmative Action or abortion. Then you would be asked to vote for which argument you found most compelling, and you would see how all visitors’ votes added up. Both sides presented were actually quite reasonable, and this really made you think and not just stick to your own ideology. But perhaps this approach would be obsolete in these polarized times! Nevertheless, kudos to the US government that designated the First Women’s Rights Convention and created a site to commemorate and explain it. I hope the present government hasn’t noticed.

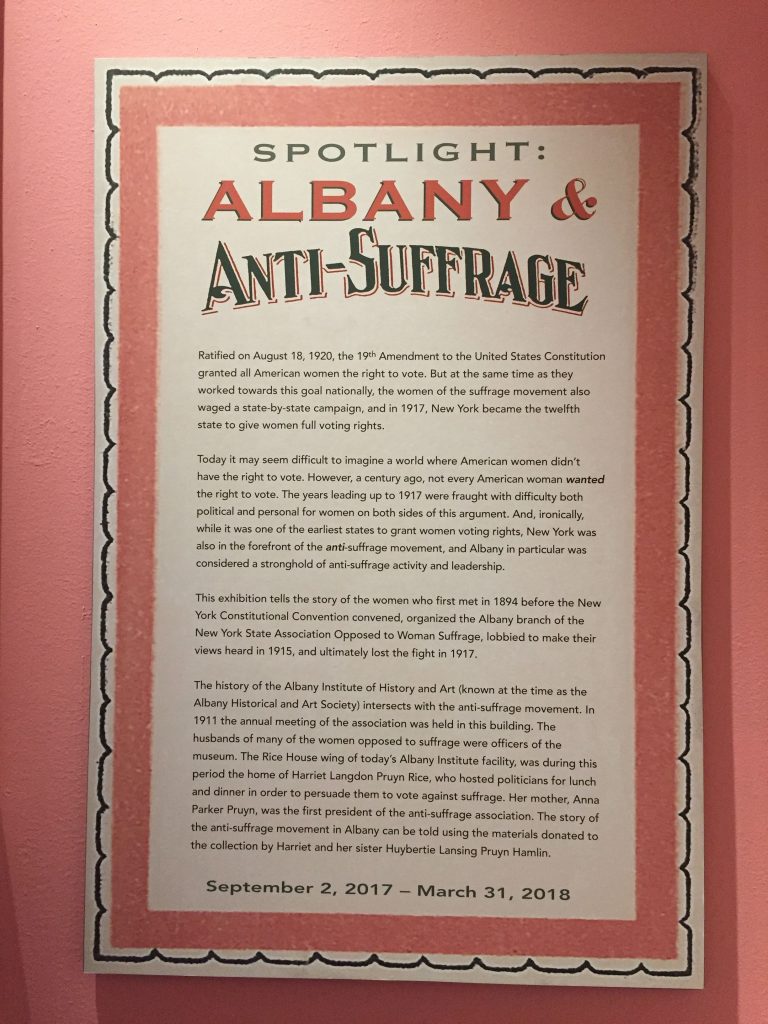

On the opposite side of the coin is an exhibition I saw last year in the US, at The Albany Institute of History & Art: “Spotlight: Albany and Anti-Suffrage” (figure 6). The exhibit follows the opposition mounted to the lead-up to 1917, when the state of New York gave women full voting rights. It tells the story of the women who organized the Albany branch of the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage. I found the topic to be presented in a thorough and sensitive manner.

As the exhibit says: “There is no suffrage story without the anti-suffrage story.”

Tina Bates

Past-Chair, OWHN

Recent Comments